- photo contests ▼

- photoshop contests ▼

- Tutorials ▼

- Social ▼Contact options

- Stats ▼Results and stats

- More ▼

- Help ▼Help and rules

- Login

Why Machinima Will Replace 3D Packages for Amateur CG Artists

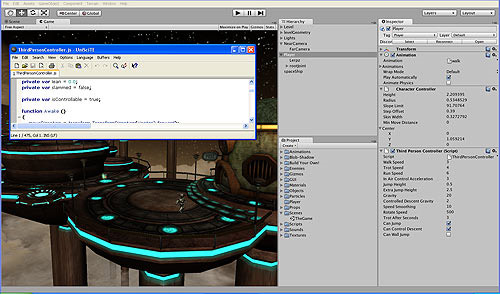

Consumer 3D packages are bulky and hard to learn. CG artists spend many years training in order to become proficient at animation, modeling, and effects. What if there was a shortcut to avoid the steep learning curve of 3D packages? This is where machinima comes in.

Though currently a staple of gaming communities, machinima has potential to become the next big thing for CG artists and content creators. It’s easily accessible, requires none or very little capital to start, and it looks better and better every year. The need for thousand-dollar CG applications becomes obviated when similar quality productions can be done in a tenth of the time for a hundredth of the budget.

Conclusion

The art of machinima is still young, but computer graphics and animation technology is raising the bar every year, providing a better and better starting point for filmmakers lacking the resources to realize their ideas. There is a lot of potential, both in marketing the idea of realtime 3D cinema and in leveraging current offerings in game and CG technology to create more involving and sophisticated art.Howdie stranger!

If you want to participate in our photoshop and photography contests, just:

LOGIN HERE or REGISTER FOR FREE

-

says:

-

says:

Like Darth above I’m a long time machinimator combining various engines, see http://www.vimeo.com/10714505 as an example. I believe that the growth of machinima within traditional filmmaking has been inhibited by a perception of its blokey gamer image. This isn’t surprising as the culture emerged from the games you mention, and picture, above. The indie machinima scene is growing rapidly at the moment, based on game-like engines but avoiding the rights issues associated with using games company assets. Moviestorm, iclone and the virtual world of Second Life are currently making the news, but new products emerge every day. It is well worth looking around for engines where the license allows you to own the movies you make, as games companies can be tricky to deal with.

( 2 years and 4833 days ago )

A very interesting article that highlights some of the reasons I got into machinima in the first place.

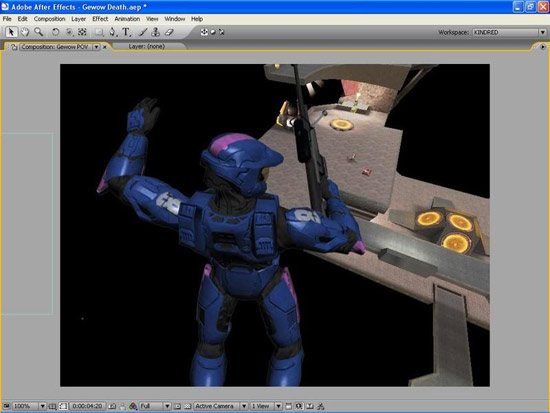

As for combining footage from two different engines, I thought I’d mention that I use this concept it alot of my machinima. For example, this film: http://darkness.bathtub-productions.com/cinema.php?vid=37

All of the scenes featuring the characters use one engine while the footage of spaceships flying around and battling each other were made with another engine. In some cases, the two were combined for the same scene, so someone could be looking out of a window at the space footage. It’s extremely effective.

( 2 years and 4834 days ago )